Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is a common vestibular disorder, affecting individuals of all ages and genders (Brevern et al., 2007). The prevalence of BPPV is estimated at 64 cases per 100,000 people annually, resulting in considerable morbidity (Froehling et al., 1991). BPPV is characterized by brief episodes of vertigo (an abnormal illusion of movement), which is brought on by certain head positions relative to gravity (Epley, 1996). Patients experiencing BPPV often report vertigo upon change in head position, nausea and occasional vomiting (Dix & Hallpike, 1952).

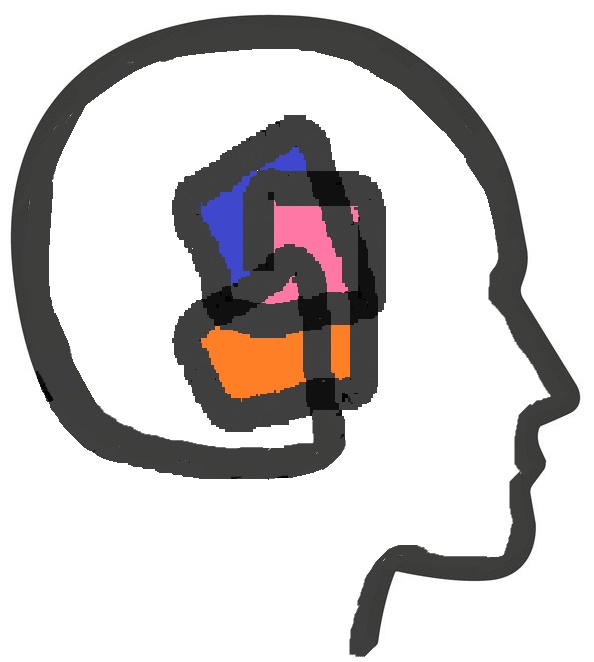

The cupulolithiasis theory and the canalithiasis theory are two hypotheses within the literature explaining BPPV. The cupulolithiasis theory is based on the idea that otolithic debris attach to the cupula and upon certain head positions, the pull of gravity deflects the weighted cupula resulting in inaccurate signalling (Schuknecht, 1969). Hall, Ruby and McClure (1979) proposed the canalithiasis theory, suggesting that free-floating debris in the semicircular canals deflect the cupula, which results in inaccurate signalling upon the change in head position. Regardless of which theory is most accurate in explaining the symptoms in any particular case, both support the notion that foreign debris is present in the semicircular canals, leading to vertigo.

Etiology:

Many potential mechanisms have been correlated with causing otoconia detachment, such as inner ear disease (viral neurolabyrinthitis), age-related degeneration, Meniere’s disease and head trauma (Johnson, 2009; Ahn et al., 2011; Motin et al., 2005). However, the exact etiology of BPPV is frequently unknown and thus labelled idiopathic. Idiopathic BPPV accounts for approximately 34 to 66 percent of cases and is thus considered to be the most common type of BPPV (Motin et al., 2005). Katsarkas (1999) explored the clinical characteristics of idiopathic BPPV in a retrospective study and found that women had a higher proportion of incidence over men.

Subjective Assessment:

The diagnosis of BPPV is based predominantly on the patient’s subjective history in combination with diagnostic testing (De Stefano, Dispenza, Di Trapani, & Kulamarva, 2008; Parnes et al., 2003). Although a standardized subjective history questionnaire does not exist when screening patients reporting vertigo, certain questions should be included when BPPV is suspected, such as; onset of symptoms, description of symptoms, provocation of symptoms, duration of symptoms, hearing changes, vision changes and neurological signs. Once a thorough history has been obtained, the clinician will need to decide which diagnostic tests are appropriate.

Objective Assessment:

Provocative manoeuvres, such as the Supine Roll test and the Dix-Hallpike test, aid in diagnosis of post-traumatic BPPV and detect semicircular canal involvement. The Supine Roll test is used for diagnosis of horizontal semicircular canal HC-BPPV (White, Coale, Catalano, & Oas, 2005). Due to the low prevalence of HC-BPPV, the Supine Roll test is not typically discussed within the literature. In contrast, the Dix-Hallpike test is a popular and highly effective provocative test used to diagnose both anterior semicircular canal (AC) and posterior semicircular canal (PC) BPPV (Dix & Hallpike, 1952). In the simplest manner, a positive test for BPPV is the presence of nystagmus and reports of vertigo upon exposure to the provocative manoeuvre (Dix & Hallpike, 1952). In conjunction with a thorough subjective history and provocative testing, exploration of BPPV frequently includes a neuro-otological examination as part of the assessment. Motin et al. (2005) and Gordon et al. (2004), used the protocol described by Zee and Fletcher to administer a neuro-otological exam. This exam includes eye movement testing, evaluation of spontaneous nystagmus with and without visual fixation, evaluation of dynamic vestibule-ocular reflex function, as well as a positioning test for PC and HC-BPPV (Zee & Fletcher, 1996).

All health content provided on ‘The Dizziness Class’ website should not be considered medical advice or a substitute for a consultation with a physician or any other primary health care provider. Our website is neither able to predict nor control unforeseeable circumstances with the information provided on its web pages. Thus, we cannot offer specific medical advice. If you are encountering any medical problem, please contact the appropriate primary health care provider. Please read our disclaimer.